The origin and function of brain oscillation

Since German neurobiologist Hans Berger first documented spontaneous rhythmic fluctuations in the human electroencephalogram. Many scholars become captivated by this phenomena and attempt to unravel its secret. This periodic change in the brain is known as brain oscillation.

Abstract

Hans Berger, a German neurobiologist, was the first to observe spontaneous rhythmic fluctuations in the human electroencephalogram [Berger 1929]. Many scholars become intrigued by this phenomena and attempt to unravel its secret. Brain oscillation is the term used to describe these periodic fluctuations in the brain. In this section, I will look at the brain oscillation from two perspectives. One is the origin of brain oscillation, which is the process that generates different forms of oscillation. The other is the function of brain oscillation, which involves various cognitive activities.

Introduction

Around 1929, German neurobiologist Hans Berger reported the first spontaneous rhythmic fluctuations in the human electroencephalogram[Berger 1929]. Following that, many scientists became interested in this phenomenon and began to extend this field. Many studies have accumulated a wealth of evidence that establishes the causal relationship between the generation of different frequencies of specific brain oscillations and neuronal cellular property, network formation [Sanchezvives et al., 2000], and specific cognitive function[Headley et al., 2017]. According to the results of human EEG research, neural oscillations have historically been classified into five frequency bands: delta (1-4 Hz), theta (4-8 Hz), alpha (8-12 Hz), beta (15-30 Hz), gamma (30-90 Hz), and high gamma (>50 Hz)[Cole et al., 2017].

The origin of brain oscillation

How is the brain oscillation generated? This question may have tormented scientists for decades. Despite numerous studies, there is still no complete and confirmed answer. Here, I will break down the question into the following sections and review research that address or are connected to the questions.

1. Are there central brain oscillation generated region and where?

2. What it the basic cellular mechanism for the brain oscillation?

3. There are many cell types that constitute the brain tissue, how does these subtypes of cells contribute to the generation of brain oscillation?

4. Did the different types of oscillation being generated in different mechanisms?

Early studies in cat suggest that thalamus will be origin of brain rhythmic activity[Andersson et al., 1971a][Andersson et al., 1971b]. Rhythmic slow wave activity has been recorded with multiple micro-electrode penetrations in the intact thalamus of the unanaesthetized cat. The result indicated that the occurrence of rhythmic activity is related to periodic excitability changes in many cells. The specialty of thalamus lies on the relay neuron found in this region which shows dramatic electrical property. The relay neurons demonstrate a dense distribution of T type Ca2+ channels in its soma and dendrites that initiation of IT(current) generally leads to an all-or- none Ca2+ spike[Sherman et al., 2009]. Such kind of firing modes are referred tonic and burst firing. Interestingly, how does the T type Ca2+ channel give the cell such property? This should go back to the structure of T type Ca2+ channels, this structure contain a two voltage sensitive motif [Talavera et al., 2006] and show various behavior at a relatively hyperpolarized resting membrane potential (about -70 mV): One is the activation gate which is closed, while another is inactivation gate which is open. Therefore the T channel is deactivated and de-inactivated [Sherman et al., 2001; Scholarpedia].

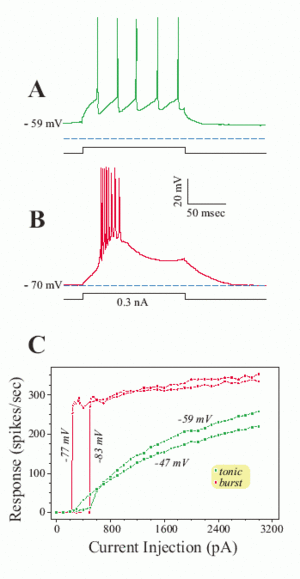

Fig.1 Different properties of the low threshold Ca2+ spike; (adapted from [Sherman and Guillery, 2006; scholarpedia/article/Thalamus]).

Fig.1 Different properties of the low threshold Ca2+ spike; (adapted from [Sherman and Guillery, 2006; scholarpedia/article/Thalamus]).

If the relay cell is relatively depolarized for ≥100 msec, T channels are inactivated and play no role in neuronal responses[Fig.1A]. Now, a depolarizing current pulse (or EPSP) directly activates a series of unitary action potentials for as long as the input remains suprathreshold; _this is the tonic mode of firing._ However, if the same cell is sufficiently hyperpolarized for ≥100 msec, T channels are de-inactivated and primed for action[Fig.1B]. Now, the very same depolarizing pulse (or EPSP) activates the low threshold Ca2+ spike, which in turn, activates a burst of 2-10 action potentials; this is the burst mode of firing.

_What’s surprising is that every relay cell in every thalamic nucleus of every species studied so far shows this behavior, and this is seen only rarely in other neuronal types in the central nervous system[Scholarpedia]._ This phenomenon draw my interest to find the deeper molecular mechanism of the selectivity and evolutionally conservativeness.

Go back to oscillation, the relationship between the brain oscillation and the T type channel was established by one report that the less active input circuit from cholinergic parabrachial to thalamus during slow-wave sleep phase promote the tendency of relay neurons to fire in the burst mode[Sherman et al., 2009] and this low Ca2+ threshold spikes tends to be synchronized and rhythmic among neurons in the thalamus[Sherman et al., 2009]. What’s more, this synchronized, rhythmic bursting depends on interactions among reticular cells and between reticular and relay cells in thalamus. It is important to note that not all thalamic cells show rhythmic bursting during slow-wave sleep and that such bursting is typically interspersed with periods of tonic firing[Sherman et al., 2009].

In the cortex, the pyramidal neurons arranged in an extreme order which give an anatomical basis for oscillation generation[Globus et al., 1967a] [Globus et al., 1967b], The reason seems that when the nerve cells are arranged in the same direction, the pyramidal cells are arranged in a regular way, and their apical dendrites reach to the surface of the cortex in the same direction[Chang et al., 1951], a larger amount of electricity can be recorded, otherwise, electrical signals travel in different directions, cancelling each other out and unable to form a strong electric field[伍国锋 et al., 2000].

The electrical properties of cortical neurons include the intrinsic electrical activity of the neurons themselves (membrane potential and its fluctuations); conductance of action potential (conduction of nerve impulses); The excitatory or inhibitory postsynaptic potential(EPSP/IPSP) produced during synaptic transmission. Sanchezvives et al. reported that using intracellular direct current injection to hyperpolarize or depolarize cortical neurons did not change either the duration of the depolarized state or the slow oscillation frequency in the recorded neuron which suggested that the slow oscillation is generated as a network event but intrinsically in the neuron recorded[Sanchezvives et al., 2000]. Generally speaking, the brain oscillation is considered to be the sum of postsynaptic potentials when the neuronal groups in the cortex synchronously being active.

Now, we will go into the question that which cell type is the major player in the generation of oscillation? It was reported that GABAergic interneurons was considered as one of the major players in generating or regulating the neuronal oscillation according to previous studies[Sohal et al., 2009][Veit et al., 2017].

Delta:

Striatal medium spiny neurons (MSNs), one of the inhibitory neurons, contain distinct neuron activity fluctuations, that is up and down[Wilson et al., 1996]Mahon et al., 2006. Upstates represent a package of EPSP and IPSP that cause a significant elevation in membrane conductance, whereas downstates are associated with decreased synaptic activity. During upstates, the mixture of excitatory and inhibitory inputs demonstrate a “balanced” state that favors the generation of gamma oscillations[Headley et al., 2017]. It is important to note that striatal upstates are not generated by local circuit interactions within the striatum, but imposed by corticostriatal neurons driving striatal interneurons and MSNs[Mahon et al., 2001]. In short, delta oscillations arise from the propagation of activity throughout the cortex and stratum delta activity depends on cortical inputs.

Theta:

Theta oscillations (4–11 Hz) are found active in the hippocampus[Buzsáki et al., 2002]. In the behaving rat, the majority of CA1 interneurons in hippocampus discharge on the descending phase of theta in the pyramidal cells layer and discharge on the ascending phase in the apical dentritic layers[Buzsáki et al., 2002]. Among the interneurons, PV expressing interneurons are found in relation with the mediation of pyramidal cell spiking resonance in the cortical network which support transmission of theta oscillation[Stark et al., 2013]. Pyramidal cell spiking resonance was basically depend on the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-sensitive (HCN) channels, which generate a nonselective cation current(Ih)[Narayanan and Johnston, 2008]. And HCN1 channels was found especially abundant in the distal apical dentrites of CA1 pyramidal cells[Stuart and Spruston, 1998]. But how does HCN1s cause the resonance? Previous study claim that Ih have an inductive effects and can create a negative feedback which opposes the voltage changes and thus creates resonance [Narayanan and Johnston, 2008].

Beta and Gamma:

After the creation of optogenetics techniques, scientists are able to manipulate genetically labeled subtype of inhibitory neurons. They find that gamma oscillations in vivo are suppressed by inhibiting PV-expressing interneurons, while driving these interneurons using optogenetics method is sufficient to generate emergent gamma-frequency rhythmicity. These evidences suggested that PV interneurons are important in the generation of gamma rhythms [Sohal et al., 2009]. For Beta basis, Rhythmic activation of SOM cells in the local circuit entrains syntonous activity in the narrow 5- to 30-Hz band(Beta)[Chen et al., 2017]. Distinct subtypes of inhibitory interneuron are known to shape diverse rhythmic activities in the cortex, but how does the different subtypes of inhibitory interneuron interact with each other to orchestrate specific band activity?

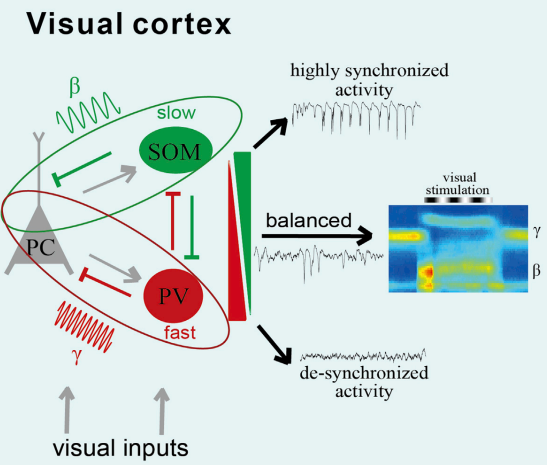

Recently, researcher reported that in the visual cortex, the firing of somatostatin (SOM) neurons was more correlated with the activity of the visually-induced beta oscillations, while the firing of parvalbumin (PV) neurons was highly correlated with the spontaneous gamma oscillations [Chen et al., 2017].

Fig.2 Distinct inhibitory interneurons orchestrate cortical beta and gamma oscillations (adapted from Chen et al., 2017)

Fig.2 Distinct inhibitory interneurons orchestrate cortical beta and gamma oscillations (adapted from Chen et al., 2017)

Through manipulating the firing activity of cell type specific neurons, they show that suppression of SOM cell spiking decrease the beta frequency band(20-30Hz) oscillation activity and promote a more “de-synchronization” state of local network activity[Chen et al., 2017]. On the other hand, inhibiting PV cell activity increases the synchronization of spontaneous activity across a broad frequency range and further blocks changes in beta and gamma oscillations due to visual stimulation. Finally, they provide a model for differential and cooperative function of different subtypes of inhibitory interneuron in orchestrating specific band oscillation activity [Fig.2]. In short, this study systematically elucidates the neural mechanism of the generation of electrical activity in local networks of different frequencies in the cerebral cortex.

The Function of brain oscillation

1. Memory and Learning

Memory is generally classified as declarative memory and procedural memory [Squire et al., 1992], which is associated with cortex/hippocampus and striatum [Foerde et al., 2006, Headley et al., 2017]. Declarative memory refers to the memory that being acquired through language transmission and its extraction [Squire et al., 1992]. Hippocampus was found being active when participant start retrieve declarative memory under discrimination task[Foerde et al., 2006]. Procedural memory, known as non-declarative memory, refers to the memory of skilled motor or perceptual behaviors. It is the connection between a stimulus and a response in general. fMRI result tell us that such kind of memory are related to striatum[Foerde et al., 2006]. Then, how does the oscillations function in these memory systems?

Basically, Theta oscillation was proved to be linked with declarative memory on the basis of the finding of the association between task performance that require declarative memory and enhanced theta coherence between the temporal lobe and hippocampal sites for recalled items [Fell et al., 2003]. It was concluded that memory process including three part, encoding, maintaining, retrieval. Theta oscillation in the hippocampus also associated with memory retrieval. When the rats express frozen behavior associated with aversive cues or situations, the coherence between theta oscillation and amygdala increased. Its coherence with the amygdala increases when rats express freezing behavior associated either with aversive cues or contexts [Seidenbecher et al., 2003]. In sum, Theta synchronization in amygdala-hippocampal pathway may be functionally underlies the retrieval and expression of conditioned fear [Seidenbecher et al., 2003]. In addition to above memory systems, Theta (4–11 Hz) oscillations was also reported to provide basis to the temporal coding of spatial information in the hippocampus [O’Keefe and Recce, 1993]. Such kind of navigation function which based on spatial memory is further supported by the hippocampal-entorhinal circuit research [Buzsáki et al., 2013].

For the dynamic regulation of memory system, oscillation operate in fast or slow mode [Headley et al., 2017]. The slow mode happens during quiet resting state and is featured by low frequency delta oscillations in cortical and striatal circuits, while the fast mode exists during active waking state and is characterized by theta oscillations in the hippocampus [Headley et al., 2017]. Last by no least, the memory consolidation is another important function where brain oscillation play a role. It was said that slow wave activity regulate the consolidation of declarative memories, the fast mode oscillation adjust the consolidation of procedural memories [Headley et al., 2017].

Learning process, in my perspective, is a two-step procedure, information loading and information processing which aim at building logic relationship between two facts or items. The interaction between medial prefrontal cortex(mPFC) and hippocampus underlie such process[Benchenane et al., 2010]. In this study, the coherence in theta oscillations between mPFC and Hippocampus in rats performing a task on Y maze was measured by researchers and they found that coherence spiked at the choice point, the strength reach highest after task rule acquisition [Benchenane et al., 2010]. One more thing that need to mention here is the disease. Neurodegenerative disorders are progressive diseases that impair central nervous system gradually. Patients with Alzheimer disease was found impaired Gamma oscillation in brain [Iaccarino et al., 2016]. Even though many experimental and clinical studies have been performed or undergoing, no effective therapy has been built. Recently, scientist tested a novel therapy method with a light flinking in certain range of frequency (gamma). It turns out the pathology in the visual cortex of AD mouse model was reduced [Iaccarino et al., 2016]. Detailed mechanism of how gamma frequency improve the disease was preliminarily claimed as the attenuation of amyloid load and microglia modification [Iaccarino et al., 2016]. Following study in this year suggests that auditory perturbing method similar to previous light flinking frequency can reduce the AD pathology and improve cognitive performance in mouse model [Martorell et al., 2019]. _Taken together, dysfunction in microglia will reveal in the abnormal oscillation of gamma band._ If we introduce some techniques to balance the oscillation, microglia’s function will go back to normal which give us hope for developing non-invasive therapy of Alzheimer disease in the future.

2. Sleep

Sleep is an interesting and mystery topic. Basically, it’s a kind of state, relative to wake. Sleep is reported as synchronized events in tons of synaptically coupled neurons in thalamocortical systems [Steriade et al., 1993]. Physiologists divide the sleep process into two major phases: slow-wave sleep and fast-wave sleep based on changes in eeg, emg, ecg and emg as well as changes in blood pressure and respiration. The brain activity in a certain time was staged as wake, sleep based on the EEG/EMG recoding, Under sleep stage, there are two phases, one is NREM(Non Rapid Eye Movement Sleep), another is REM(Rapid Eye Movement Sleep). Briefly, wake was defined by low amplitude, fast EEG and high amplitude, variable EMG; NREMs by high amplitude, delta (1–4 Hz) frequency EEG and low EMG band; REMs by significant theta (6–9 Hz) frequency EEG and EMG band [Funato et al., 2016]. Based on current finding, organisms show no consciousness during sleep. The underling mechanism in neural circuit level and molecular level are still unsolved and only a little evidences being accumulated [Weber et al., 2015, Wang et al., 2018]. The purpose of sleep or the necessity of sleep is associated with memory consolidation, brain metabolism regulation. Sleep deprivation will induce the death and this is evidenced by both human clinical trials [Dinges et al., 1995] and animal researches [Everson et al., 1989]. A good quality of sleep make a person full of spirit and power in a new day. However, sleep disruption or dysfunction could induce disorder like Insomnia, Narcolepsy. One is Loss of sleep, another is too much or uncontrolled/paroxysmal sleep. Both type of disorder give our society a lot of burden and deeper understanding of how sleep work is necessary. Since sleep is associated with the characteristic patterns of power spectrum in the EEG, you may ask how and where did they come from? Here we focus on the oscillation that associated sleep. In addition to the neuronal projection and firing basis that we elucidate previously, _neurotransmitter system is also involved in the regulation of brain oscillation associated with sleep._ It was reported that the periodicity of NREM and REM sleep can be modeled as an antagonistic interaction between REM-ON (cholinergic) cells and REM-OFF (serotonergic, noradrenergic and histaminergic) cells [Kandel et al., 2004]. What’s more, the activation of a variety of neuro-modulatory transmitter systems during awakening will prohibit oscillations of low frequency, induce fast rhythms, and bring the brain to full responsive recovery [Steriade et al., 2004]. Above is all for this short review. Brain oscillation is a big topic and is hard to go through more details. _In summary, brain oscillation serve an inner representation of the cognitive behaviors of one individual and the fantastic molecular and cellular architecture of the brain tissue provide basis for that._

References

-

Berger, Hans. “Über das elektrenkephalogramm des menschen.” European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience 87.1 (1929): 527-570.

-

Wang, X.J. (2010). Neurophysiological and computational principles of cortical rhythms in cognition. Physiol. Rev. 90, 1195–1268.

-

Cole, Scott R., and Bradley Voytek. “Brain Oscillations and the Importance of Waveform Shape.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 21.2 (2017): 137-149.

-

Sherman, S. Murray. “Tonic and burst firing: dual modes of thalamocortical relay.” Trends in Neurosciences 24.2 (2001): 122-126.

-

Talavera, Karel, and Bernd Nilius. “Biophysics and structure–function relationship of T-type Ca2+ channels.” Cell Calcium 40.2 (2006): 97-114.

-

Andersson, S. A , and J. R. Manson . “Rhythmic activity in the thalamus of the unanaesthetized decorticate cat.” Electroencephalography & Clinical Neurophysiology 31.1(1971):0-34.

-

Andersson, S. A , E. Holmgren , and J. R. Manson . “Synchronization and desynchronization in the thalamus of the unanesthetized decorticate cat.” Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology 31.4(1971):335-345.

-

Sherman, S. Murray , and R. W. Guillery . Exploring the Thalamus and Its Role in Cortical Function. MIT Press, 2009.

-

Globus, Albert, and A. B. Scheibel. “Synaptic loci on visual cortical neurons of the rabbit: the specific afferent radiation.” Experimental neurology 18.1 (1967): 116-131.

-

Globus, Albert, and Arnold B. Scheibel. “Pattern and field in cortical structure: the rabbit.” Journal of Comparative Neurology 131.2 (1967): 155-172.

-

Chang, Hsiang-Tung. “Dendritic potential of cortical neurons produced by direct electrical stimulation of the cerebral cortex.” Journal of neurophysiology 14.1 (1951): 1-21.

-

伍国锋, and 张文渊. 脑电波产生的神经生理机制. Diss. 2000.

-

Sanchezvives, Maria V., and David A. Mccormick. “Cellular and network mechanisms of rhythmic recurrent activity in neocortex.” Nature Neuroscience 3.10 (2000): 1027-1034.

-

Wilson, C. J. & Kawaguchi, Y. The origins of two-state spontaneous membrane potential fluctuations of neostriatal spiny neurons. J. Neurosci. 16, 2397–2410 (1996).

-

Mahon, S. et al. Distinct patterns of striatal medium spiny neuron activity during the natural sleep-wake cycle. J. Neurosci. 26, 12587–12595 (2006).

-

Headley, Drew B., and Denis Paré. “Common oscillatory mechanisms across multiple memory systems.” npj Science of Learning 2.1 (2017): 1.

-

Mahon, and S. “Relationship between EEG Potentials and Intracellular Activity of Striatal and Cortico-striatal Neurons: an In Vivo Study under Different Anesthetics.” Cerebral Cortex 11.4(2001):360-373.

-

Narayanan, R. , and D. Johnston . “The h Channel Mediates Location Dependence and Plasticity of Intrinsic Phase Response in Rat Hippocampal Neurons.” Journal of Neuroscience 28.22(2008):5846-5860.

-

Stark, Eran, et al. “Inhibition-induced theta resonance in cortical circuits..” Neuron 80.5 (2013): 1263-1276.

-

György Buzsáki. “Theta Oscillations in the Hippocampus.” Neuron 33.3(2002):0-340.

-

Kopell, N , et al. Gamma and Theta Rhythms in Biophysical Models of Hippocampal Circuits. Hippocampal Microcircuits. Springer New York, 2010.

-

Sohal, Vikaas S., et al. “Parvalbumin neurons and gamma rhythms enhance cortical circuit performance.” Nature 459.7247 (2009): 698-702.

-

Chen, Guang , et al. “Distinct Inhibitory Circuits Orchestrate Cortical, beta, and, gamma, Band Oscillations.” Neuron 96.6(2017):1403-1418.e6.

-

Veit, J., Hakim, R., Jadi, M. et al. Cortical gamma band synchronization through somatostatin interneurons. Nat Neurosci 20, 951–959 (2017).

-

Foerde, Karin, Barbara J. Knowlton, and Russell A. Poldrack. “Modulation of competing memory systems by distraction.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103.31 (2006): 11778-11783.

-

Squire, L. R. Declarative and nondeclarative memory: multiple brain systems supporting learning and memory. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 4, 232–243 (1992).

-

Seidenbecher, T., Laxmi, T. R., Stork, O. & Pape, H. C. Amygdalar and hippocampal theta rhythm synchronization during fear memory retrieval. Science 301, 846–850 (2003).

-

Fell, J. et al. Rhinal-hippocampal theta coherence during declarative memory formation: interaction with gamma synchronization?. Eur. J. Neurosci. 17, 1082–1088 (2003).

-

Okeefe, John, and Michael Recce. “Phase relationship between hippocampal place units and the EEG theta rhythm.” Hippocampus 3.3 (1993): 317-330.

-

Buzsáki, György, and Edvard I. Moser. “Memory, navigation and theta rhythm in the hippocampal-entorhinal system.” Nature neuroscience 16.2 (2013): 130.

-

Stern, Edward A., Dieter Jaeger, and Charles J. Wilson. “Membrane potential synchrony of simultaneously recorded striatal spiny neurons in vivo.” Nature 394.6692 (1998): 475.

-

Headley, Drew B., and Denis Paré. “Common oscillatory mechanisms across multiple memory systems.” npj Science of Learning 2.1 (2017): 1.

-

Benchenane, Karim, et al. “Coherent theta oscillations and reorganization of spike timing in the hippocampal-prefrontal network upon learning.” Neuron 66.6 (2010): 921-936.

-

Iaccarino, Hannah F., et al. “Gamma frequency entrainment attenuates amyloid load and modifies microglia.” Nature 540.7632 (2016): 230.

-

Martorell, Anthony J., et al. “Multi-sensory Gamma Stimulation Ameliorates Alzheimer’s-Associated Pathology and Improves Cognition.” Cell (2019).

-

Kandel, E.R., Schwartz, J.H. and Jessell, T.M. eds., 2000. Principles of neural science (Vol. 4, pp. 1227-1246). New York: McGraw-hill.

-

Weber, Franz, et al. “Control of REM sleep by ventral medulla GABAergic neurons.” Nature 526.7573 (2015): 435.

-

Wang, Zhiqiang, et al. “Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of the molecular substrates of sleep need.” Nature 558.7710 (2018): 435.

-

Funato, Hiromasa, et al. “Forward-genetics analysis of sleep in randomly mutagenized mice.” Nature 539.7629 (2016): 378.

-

Dinges, David F., et al. “Sleep deprivation and human immune function.” Advances in neuroimmunology 5.2 (1995): 97-110.

-

Everson, C. A., Bergmann, B. M., & Rechtschaffen, A. (1989). Sleep deprivation in the rat: III. Total sleep deprivation. Sleep, 12(1), 13-21.

-

Steriade, Mircea. “Acetylcholine systems and rhythmic activities during the waking–sleep cycle.” Progress in brain research 145 (2004): 179-196.

-

Steriade, Mircea, David A. McCormick, and Terrence J. Sejnowski. “Thalamocortical oscillations in the sleeping and aroused brain.” Science 262.5134 (1993): 679-685.

-

Benchanane, K. et al. Coherent theta oscillations and reorganization of spike timing in the hippocampal-prefrontal network upon learning. Neuron 66, 921–936 (2010).